Key Points:

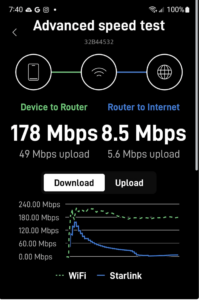

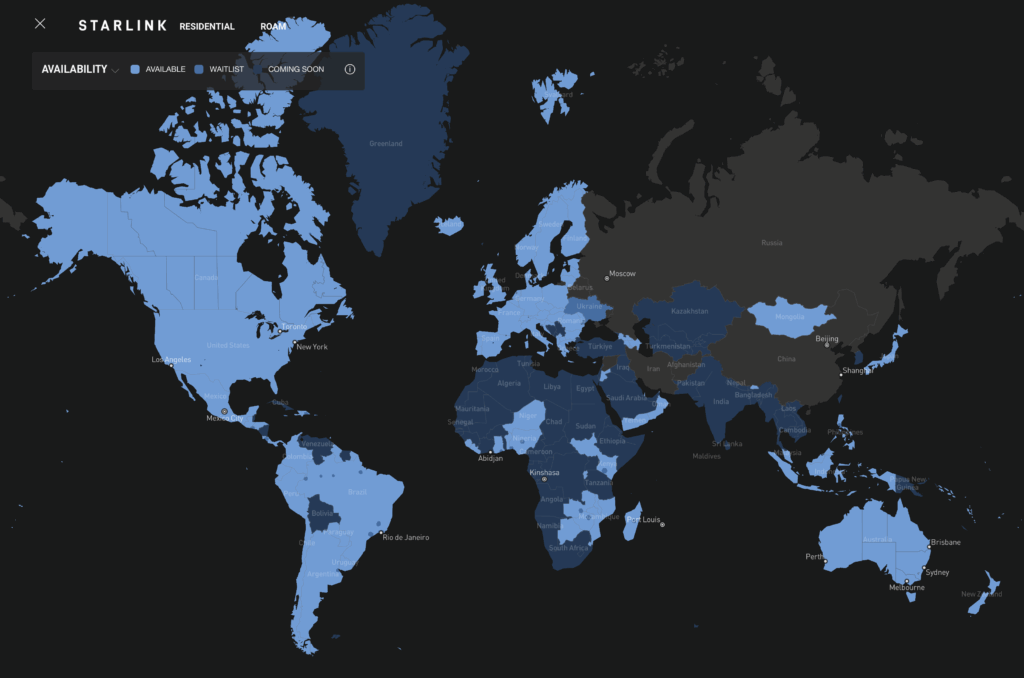

- SpaceX's Starlink continues to dominate satellite internet, and a new generation of Starlink V3 satellites has the potential to bring an order of magnitude more capacity online.

- Amazon's Project Kuiper has at last begun its launch campaign, and Amazon may have some level of satellite broadband service available by the end of 2025.

- Satellite communication directly to cell phones is becoming a reality, with more providers looking to enable text messaging (and beyond) this year.

- Satellite and cellular remain complementary technologies, and they just keep getting better.

We have tracked satellite internet options for nomads from the very start here at the Mobile Internet Resource Center, and things have sure come a long way since our days of using a surveyor's tripod to tediously aim a huge HughesNet dish between the trees to get online from the most remote campsites.

Now, you can carry satellite broadband in a backpack and easily stream from space while in motion. Even everyday cellular phones are beginning to send and receive text messages directly via satellites.

In many ways, it is science fiction brought to life.

And for the most part, it just keeps getting better, faster, and cheaper.

This featured article provides a big-picture look at the current state of the space race as of mid-2025.

Starlink may seem like the only game in town, but there are a lot of other companies up to some very interesting things as well.

Read on for updates from all the players...

Table of Contents

Amazon’s Project Kuiper Blasts Off!

The biggest recent news in the satellite internet world is that Amazon's Project Kuiper is finally off the drawing board and on the launch pad.

We have tracked Project Kuiper since 2019, when Amazon first revealed its plans to build a global broadband satellite internet constellation designed to rival Starlink.

Amazon claims that it is setting out "to build the most advanced and the most modern communications system in the world" and "the most advanced satellite network ever built."

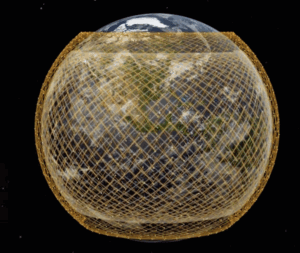

The Kuiper constellation will consist of 3,232 laser-interconnected satellites, deployed over more than 80 launches in the years ahead.

This total is far fewer satellites than SpaceX has already launched to build out Starlink, and Amazon is years behind.

But Amazon has intentionally decided to bet on being the tortoise in the race against its rapid rival, SpaceX. Amazon must clearly think Kuiper will have something special to offer.

Will Kuiper be enough to tempt people away from Starlink?

Kuiper vs Starlink: Similarities and Differences

Kuiper and Starlink have a similar design philosophy and similar overall architectures.

Both rely on massive constellations of satellites interlinked via lasers to build a mesh network in orbit. User terminals link directly to a satellite via a phased-array antenna. Then, data passes between satellites via the laser interconnects before connecting to a ground station and the broader Internet.

SpaceX's constellation has more satellites in somewhat lower orbits, which gives it a potential latency and signal strength advantage. To minimize latency, SpaceX has also started co-locating its ground stations with Google data centers.

Kuiper satellites work similarly and will route through ground stations co-located with Amazon's AWS server infrastructure. This taps into Amazon's global internet backbone, which is closely connected to the heart of the Internet.

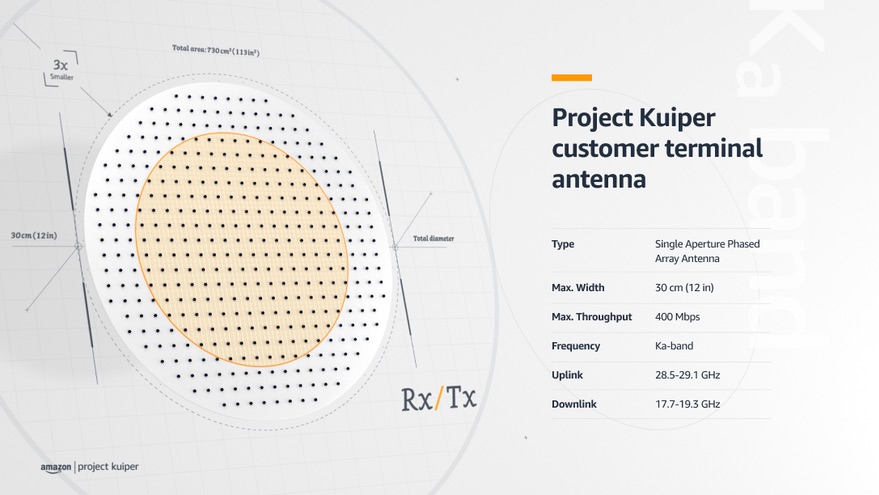

One interesting way that Kuiper will distinguish itself from Starlink is by using Ka band signals for user terminal communications. By contrast, Starlink uses the lower-frequency Ku band to user terminals, only using Ka band to communicate with ground stations.

- Kuiper User Terminal Frequency Bands: 28.5 - 29.1 GHz Uplink, 17.7 - 19.3 GHz Downlink

- Starlink User Terminal Frequency Bands: 14.0 - 14.5 GHz Uplink, 10.7 - 12.7 GHz Downlink

In general, Amazon appears to be focused on using higher frequencies for user terminals, both uplink and downlink.

Higher frequencies generally have the potential for more bandwidth and higher speeds, more tightly focused beams, and higher performance from smaller antennas. However, higher frequencies are also more susceptible to atmospheric interference and might thus be more strongly impacted by rain or snow or signal strength drop offs over distance.

Because of these core technical differences, direct head-to-head testing of Starlink versus Kuiper will be interesting indeed.

Kuiper Terminal Update

Amazon has been building factories and signing launch contracts to start full-scale Kuiper deployment. In a teaser video accompanying the first production launch on April 28th, Amazon shared that Kuiper customer terminal designs are now finalized, and production is ramping up to build "tens of millions" of these terminals.

Amazon is clearly getting ready for a large consumer launch.

Amazon previously provided basic information on three Kuiper terminals, which might not fully represent the finalized designs:

- Small - An ultra-compact and "lower cost" design measuring 7 inches square and weighing just 1 pound. This design was claimed to be capable of 100 Mbps.

- Medium - The standard Kuiper terminal is 11" square, 1" thick, and weighs 5 pounds. Amazon claims to be able to produce this terminal for "less than $400" and that it will be capable of 400 Mbps speeds.

- Large - The professional / enterprise Kuiper receiver is 19" x 30" and can perform up to 1 Gbps.

It is unclear how these teased details might have changed now that the design is finalized and in production, but hopefully, we will know more later in 2025.

Kuiper Constellation Update

Before Amazon can begin deploying Kuiper terminals to customers, it needs to put enough satellites in orbit to offer a minimal level of service.

According to FCC filings, Amazon will be able to offer coverage across "most of North America" with 578 satellites deployed, out of the planned total of 3,232 satellites in the first-generation Kuiper constellation.

Amazon's most recent update video claims that they have built production and integration infrastructure capable of preparing five Kuiper satellites per day for launch. To get Kuiper satellites to space, Amazon signed launch contracts with ULA, Arianespace, Blue Origin, and even arch-rival SpaceX.

The clock is ticking—if Amazon does not deploy at least half of its licensed satellites by July 2026, it will be in violation of the terms of its FCC license.

Kuiper has slipped so much that if it stumbles any further with this launch campaign, it may need to petition the FCC for a license waiver or extension.

Kuiper - Will It Rival Starlink?

Amazon has huge financial resources and patience, but does it have what it takes to build a true Starlink alternative?

Getting the first Kuiper launch into orbit is only the beginning.

The real test will be how quickly Amazon can launch a second, third, and follow-on Kuiper launches and deployments.

If Kuiper satellites start launching at a steady pace, Amazon will feel comfortable sharing more about Kuiper's ultimate consumer pricing, availability, performance, and other details.

Amazon's Kuiper FAQ page still claims that Amazon hopes to have some sort of Kuiper service available to customers by the end of 2025 - a likely unrealistic goal unless everything goes absolutely perfectly from here on out.

Whether Kuiper comes online for customers in late 2025 or mid-2026, the pieces are finally coming together.

Meanwhile, SpaceX is not sitting still...

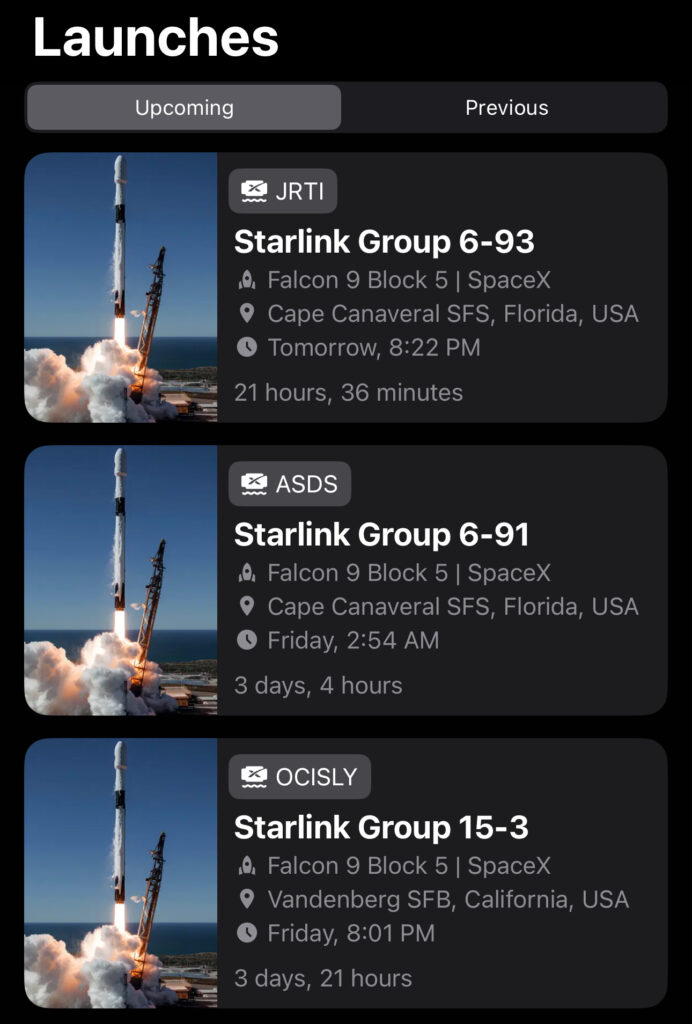

Starlink - V3 Satellites Stuck Waiting For Starship

The key to Starlink's success has been SpaceX's revolutionary reusable Falcon 9 rocket.

Booster reuse and the massive reduction in the cost-to-orbit make it economically feasible to build massive satellite constellations. Since SpaceX owns both the Falcon 9 launcher and Starlink constellation, it is able to offer itself the best possible pricing for a ride to orbit.

This has been the key competitive advantage that has allowed SpaceX to launch so many more Starlink satellites into orbit than the combined totals of what every other country or company has launched.

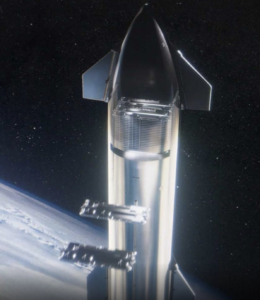

But Starlink was envisioned from the start with something even bigger in mind: Starship.

SpaceX's Starship is the largest rocket ever built. When the system is fully operational and rapidly reusable, it will be capable of delivering more cargo into orbit per launch, vastly more affordably than even the Falcon 9.

Starship absolutely dwarfs SpaceX's workhorse Falcon 9 rocket and even towers over historic giants like the Saturn 5 that took humans to the moon.

From the beginning, SpaceX's Starlink business plan was designed around the capabilities of the second-generation V2 Starlink satellites and the massive Starship launch system that would put them in orbit.

As we covered back in November 2021, at one point, Elon Musk warned SpaceX employees that SpaceX faced a genuine risk of bankruptcy unless it launched the second-generation Starlink satellites on Starship twice a month by the end of 2022.

That goal of launching Starlink V2 satellites on Starship in 2022 was obviously massively missed.

However, as Starship's schedule slipped, SpaceX pivoted and developed a smaller, less capable version of the second-generation Starlink satellite design that could fit on the Falcon 9. The "V2 Mini" has become the foundation that has allowed the Starlink constellation to thrive.

But instead of up to 60 Starlink V1 satellites per launch, only 27 V2 mini-satellites can be launched on a Falcon 9 at once. This has slowed down the pace of the Starlink constellation's growth. And when V2 Mini satellites began to feature a piggyback Direct-2-Cell payload, only 20-23 could be carried aloft simultaneously.

The Falcon 9 is just maxed out, and the next generation of Starlink capabilities is on hold, waiting for Starship.

But it looks like Starship may be ready for commercial service later in 2025, and the true next generation of Starlink satellites can begin to launch, and the upgrade appears to be massive.

Now known as Starlink V3, these new sized-for-Starship satellites are massively larger and more capable than anything that could ever be launched on the Falcon 9.

Starlink V3 Satellites - A Massive Upgrade!

SpaceX's 2024 annual Starlink progress report revealed the first details of Starlink V3 satellite capabilities.

The capability increase is huge, thanks to the physically larger (approximately 1900 kg vs. 575 kg) satellites, which have more solar and computing power available.

Here are the details - comparing each launch of Starship and Starlink V3 to the existing Falcon 9 and Starlink V2 Mini:

- Payload Mass: Starship can carry a 100-ton Starlink payload to orbit per launch versus 17 tons for Falcon 9.

- Satellites Per Launch: Starship should be capable of carrying 54 V3 satellites per launch, more than twice the 20-23 V2 Mini satellites that recent Falcon 9 launches have been carrying.

- Bandwidth Per Launch: Each Starship launch will bring 60 Tbps per second of additional Starlink bandwidth into orbit - 20 times (!!!) what each Falcon 9 launch is capable of.

- Cost Per Launch: The Falcon 9 pioneered having a reusable first stage and payload fairings, but the second stage is still discarded with every launch. Starship, on the other hand, is designed to be fully reusable. Because of this, despite being so much bigger, when full reusability is achieved, each Starship launch should cost less than a Falcon 9 launch!

Comparing the individual V3 satellites with the V2 Mini - SpaceX has said that each V3 Starlink satellite will have 1 Tbps of user downlink speeds and 160 Gbps of uplink capacity.

Compared to the V2 Mini, which was already a 4x upgrade over the first generation of Starlink satellites:

- Total User Downlink Bandwidth: 1 Tbps vs 96 Gbps

- Total User Uplink Bandwidth: 160 Gbps vs 6.7 Gbps

- Ground Station & Laser Interconnect Bandwidth: 4 Tbps vs 1.3 Tbps

Overall, this is 10x the downlink and 24x the uplink capacity of the V2 Mini Starlink satellites.

This means that each satellite will be able to serve more customers without experiencing congestion, and hopefully, end-user speeds might increase too.

Starship Testing Failures - A Major Setback For Starlink?

The Starlink V3 satellites are reportedly ready to go, but Starship is not. Yet.

One key goal of Starship's seventh test flight in January 2025 was to be the first test of the innovative "Pez Dispenser" satellite deployment mechanism, which would allow Starship to deploy a stack of up to 54 Starlink V3 satellites, one at a time, out of a side hatch.

This test flight was the first to carry this deployment system and ten dummy payloads, the size and weight of an operational Starlink V3 satellite.

The dummy satellites would test the deployment system and then burn up - and the Starship itself would then have ideally made a pinpoint soft sacrificial landing on the ocean, carefully observed by remote cameras.

Unfortunately, Starship had a major failure during launch and disintegrated spectacularly over the Caribbean long before any satellite deployment testing could be completed.

SpaceX suffered another major setback on March 6th, 2025, when the eighth Starship test flight failed even earlier in its mission than the seventh.

This mission was supposed to be a repeat of the prior failed launch, including testing the Starlink V3 deployment system.

Two nearly identical failures in a row is highly unusual for SpaceX, and this might ultimately prove to be a big setback for SpaceX (and Starlink) if it is determined that some key components need to be redesigned.

The next Starship do-over test launch could happen in late May or June 2025.

When this ninth test flight ultimately happens, SpaceX's key goal will be to complete the testing that failed in January.

For more on why Starship is critical to the future of Starlink, see our video filmed at the launch pad back in January.

Starlink: What Next?

Once SpaceX is able to resolve the issues with Starship blowing up on its way to orbit, it is expected that SpaceX will quickly start launching production Starlink V3 satellites on future test flights as they work out the procedures required to safely bring back the Starship for landing and reuse.

SpaceX has already seemingly perfected landing the first stage Super Heavy booster, so it makes economic sense for Starship to go into service deploying Starlink V3 satellites, even if it is still an experimental system and the Starship itself is not yet capable of returning to the launch pad to be reused.

SpaceX is OK with putting its own payloads at risk while the system is being developed.

Once Starship is fully reusable, SpaceX will certainly move to quickly phase out the Starlink V2 Mini design in favor of its new big brother.

As with all things SpaceX, the timing is hard to predict. The company's "failure is an option" rapid development process means that setbacks are certain, but the assembly line is always cranking out more hardware to test and refine with minimal downtime.

Overall, it would be surprising if 2025 ends without at least some Starlink V3 satellites entering service.

For more on Starlink - including the hardware and plans we recommend, check out our free and regularly updated guide focused on all things Starlink:

Starlink Satellite Internet for Mobile RV and Boat Use

Learn More:

Starlink's Referral FAQ.

Use our referral link when purchasing equipment from Starlink.com and activating a consumer Residential or Roam Unlimited data plan - and get a FREE month of service!

And so will someone on our team, which helps us keep our multiple lines of service active for continued testing.

It's a win-win - you save money and help support MIRC!

Satellite Direct To Cellular

The other seismic shift in the world of satellite internet is likely already in your pocket - satellite "direct to cellular" technology is increasingly becoming mainstream!

But this is NOT the same thing as satellite broadband!

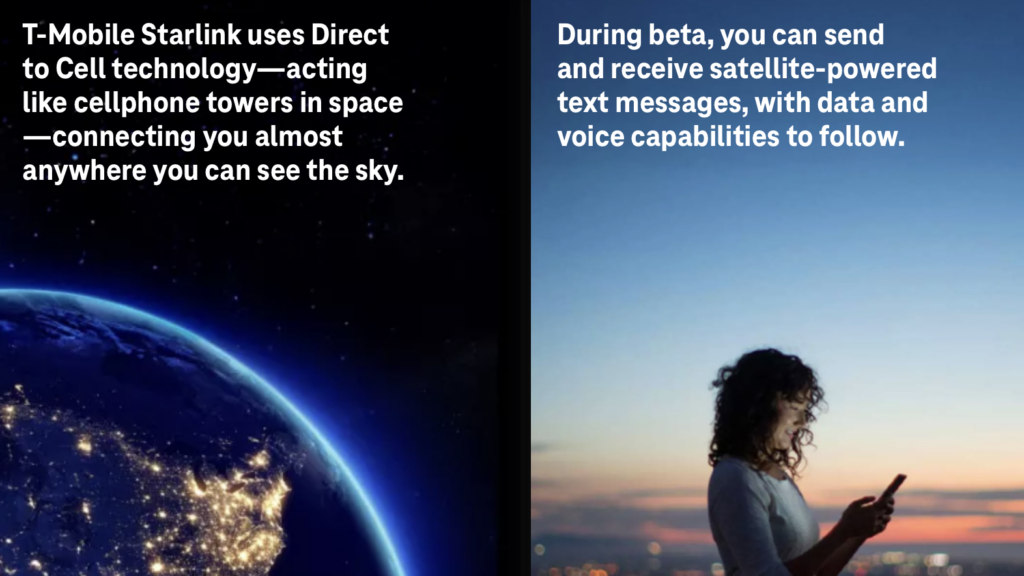

Direct-to-cellular service is meant to complement and work in partnership with traditional cellular carriers, not compete with them.

Basically, direct-to-cellular providers are building "cell towers in space" that use the same 4G or 5G standards and frequency bands as traditional carriers.

Since these cellular transmitters are in motion, zooming past hundreds of miles overhead, the laws of physics mandate that the signal will be weaker (and thus slower) than from a physically nearby tower.

And since the satellite beams are large and cover a huge area (imagine a single cell tower trying to cover an entire state), customers over a huge area will share tiny bandwidth slivers.

In other words, if a real earthbound cellular tower is in range, it will deliver better performance. These systems will NOT replace cell towers.

But - there are plenty of places where cellular towers will never be built, and direct-to-cellular provides a way for carriers to offer basic coverage in terrestrial cellular dead zones.

This is ultimately pretty amazing.

Even though the first generation of direct-to-cellular is only focused on low-bandwidth text messaging, this level of connectivity can be life-saving when you are in the middle of nowhere.

As this technology matures and more direct-to-cellular bandwidth is deployed, eventually, the capabilities will expand beyond text messaging to include voice and video calling and even low-bandwidth (compared to terrestrial cellular) data connections.

Direct to Cellular (D2C) vs Direct to Device (D2D)

Direct to Device is an umbrella term that covers satellite communications that involve any type of direct satellite link to a user device.

This includes both cellular and non-cellular devices.

Non-cellular devices include all sorts of Internet of Things (IoT) devices that can directly connect via satellite - including emergency beacons and satellite communicators that have been around for years. New technological advancements and cost reductions in this area will enable everything from monitoring the levels of water tanks on remote farms to tracking vehicles or shipping containers anywhere in the world.

Direct-to-cellular providers focus on coexisting with legacy cellular technology and frequency bands so that they can work with existing cellular devices and carriers. Direct-to-device providers, on the other hand, aren't concerned with backward compatibility, and they are typically using satellite-exclusive frequencies and custom radios rather than trying to coexist with terrestrial cellular carriers.

The lines between D2C and D2D are blurry, however. Some cellular device makers have used custom radios utilizing satellite-exclusive frequencies to communicate with D2D satellites. In particular, Apple's partnership with Globalstar and Google and Verizon using Skylo are taking advantage of legacy satellite frequency bands instead of traditional cellular signals.

As the 5G cellular standards continue to evolve to better support non-terrestrial networks, the line will blur even further as the industry develops ways to integrate these proprietary satellite networks with 5G and future 6G cellular networks.

Here is the latest on the various satellite direct-to-cellular and direct-to-device platforms...

Apple & Globalstar

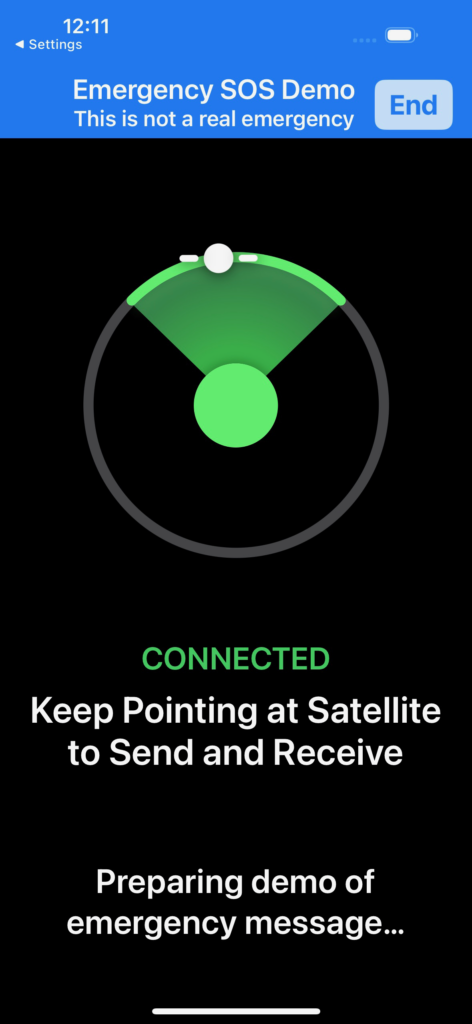

Apple was the first to bring satellite connectivity to smartphones, integrating support for emergency messaging via satellite into every iPhone since the iPhone 14 launch in 2022.

Apple has since expanded this initial emergency-only support to include location tracking and basic SMS and iMessage text messages. This keeps Apple customers in supported territories messaging anywhere they can get a clear view of the sky, regardless of cellular coverage.

This service is built in partnership with legacy satellite provider Globalstar, and it utilizes Globalstar's existing satellites and licensed spectrum rights.

This is how Apple was able to jump ahead of everyone else - not waiting for more generalized direct-to-cell technologies.

Apple purchased a major stake in Globalstar, and Globalstar has committed to devoting 85% of its current and future satellite capacity towards Apple. Apple is also providing a huge influx of cash upfront that will allow Globalstar to launch a significantly upgraded constellation of new satellites that should be fully online by 2026.

This third-generation GlobalStar constellation currently appears to be on track to start launching in mid-2025.

With a huge investment like this in play, it is clear that Apple very likely has broader future satellite ambitions beyond basic SOS and text messaging services.

But Apple's notorious secrecy means that we'll likely learn few details about what is planned until new services are ready to launch.

Starlink & T-Mobile

Apple was the first to integrate satellite connectivity into a cellular service by piggybacking on a legacy satellite system and building custom hardware into iPhones to enable this.

SpaceX is pursuing a different piggyback strategy, installing a secondary direct-to-cellular payload riding along on a subset of deployed Starlink V2 Mini (and future) satellites.

Starlink's Direct to Cell service emulates a terrestrial cell tower, using standard cellular 3GPP protocols on existing cellular spectrum. It's a "cell tower in space" that connects similarly to how domestic roaming works - a cell phone will only connect via Starlink when no terrestrial cellular option is available.

Starlink doesn't own any cellular spectrum, so it can't offer its own independent cellular service. To offer any cellular signal at all, it needs both approval from regulatory agencies and a terrestrial cellular partner willing to give up some of its airwaves.

In the USA, this partner is currently T-Mobile, though SpaceX indicated that exclusivity will eventually run out and that it may also eventually partner with other carriers.

Starlink's direct-to-cell service is launching using a sliver of T-Mobile's existing 1900 MHz cellular frequency band (LTE Band 25) and 4G transmission standards. This means that it is technically compatible with almost all existing 4G cellular devices. However, regulatory and certification hurdles mean that only phones launched in the past few years will likely be fully supported.

Satellites are much more distant than terrestrial cell towers and only provide a fraction of the bandwidth to cover a much larger area than a terrestrial cell tower. This means much lower performance.

Direct to Cell is NOT meant to be Starlink broadband service for cell phones!

Elon Musk posted on X, trying to manage expectations about what Direct to Cell will be capable of:

"Note, this only supports ~7Mbps per beam and the beams are very big, so while this is a great solution for locations with no cellular connectivity, it is not meaningfully competitive with existing terrestrial cellular networks."

But regardless of the performance limitations, it is pretty amazing that space-based messaging is being made available on cell phones that many customers already own, without requiring a new or special device.

Starlink's direct-to-cellular messaging service is currently in beta and available to T-Mobile customers. During the beta period, T-Mobile is also offering a free trial for those with primary plans on other carriers.

Assuming all goes well, the beta will end and service will officially launch over the summer.

For more, see our recent coverage:

Heading into the future, SpaceX's huge advantage will be its pace of launch, which will rapidly add more capacity to the network to enable voice and video calling and even general data connections.

AST SpaceMobile - Verizon and AT&T

Though SpaceX is unrivaled in hogging the headlines, AST SpaceMobile is another company competing in the direct to cell area.

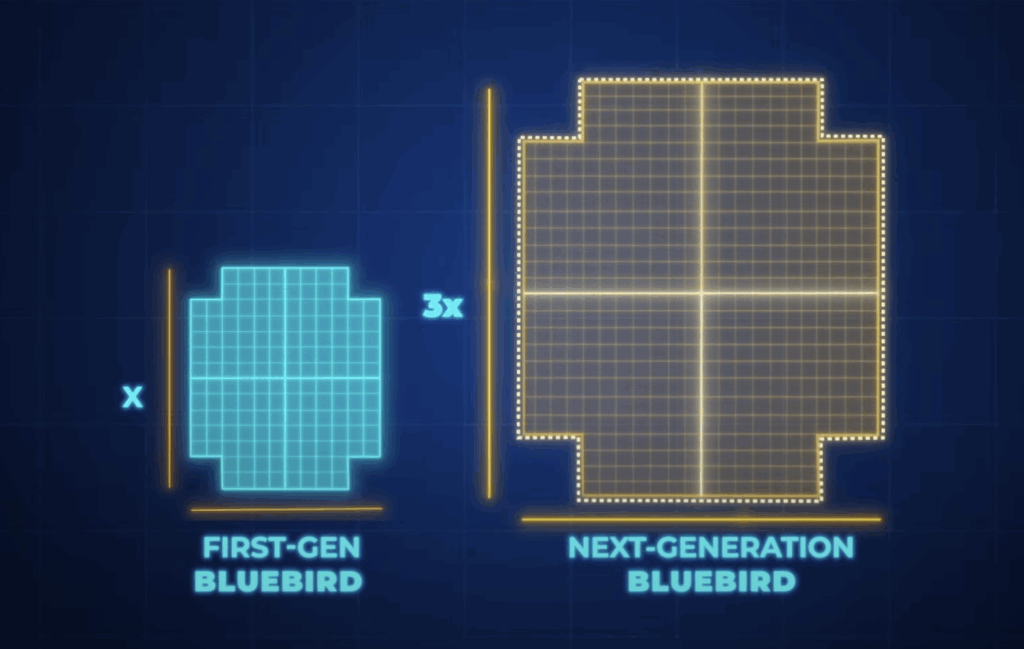

After several years of smaller-scale tests, AST SpaceMobile, in partnership with AT&T, began testing its full-scale BlueWalker 3 prototype satellite in orbit in late 2023.

Because the BlueWalker's antennas are so enormously large, SpaceMobile claims they are sensitive enough to communicate with phones even when they are indoors!

Antennas this large should make it easier to offer broadband speeds beyond just basic messaging.

SpaceMobile demonstrated satellite video calling and 5G broadband data connections with the BlueWalker test satellite and has now begun to launch its BlueBird production satellites, which will be used for commercial service.

With the technology seemingly proven, AT&T and now Verizon (see our story) have both announced partnerships with AST SpaceMobile to fund future launches to bring satellite connectivity to their customers.

It will take somewhere between 45 and 60 SpaceMobile satellites (out of an ultimate planned total of 243) in orbit before SpaceMobile can roll out full service (directly or via its carrier partners) and offer 24/7 coverage of the continental United States.

Until more satellites are available, Verizon and AT&T are looking to use SpaceMobile for limited emergency messaging capabilities.

AST SpaceMobile has launched five first-generation BlueBird satellites (in September 2024) so far and is now preparing for the next-generation BlueBird, which will be even larger and more capable.

Launches are slated to begin in mid-2025 and continue into 2026.

Lynk

In 2020, Lynk was the first company to demonstrate sending a text message from a satellite to a normal, unmodified cellphone.

Now Lynk has ambitious plans to commercialize that technology and build a 5,000-satellite constellation that enables messaging, voice calls, and more in partnership with terrestrial carriers.

Until enough of the Lynk constellation is built out to provide 24/7 coverage, Lynk only supports non-realtime messaging.

Lynk messages currently take up to 30 minutes to go through since the Lynk satellites do not yet provide 24/7 coverage.

Lynk does not have spectrum rights of its own, so it can only operate in locations where it has a partnership with a local cellular carrier that is willing to share spectrum with Lynk in return for a cut of the roaming fees.

Lynk has signed up carrier partners in many countries around the world, including Rogers in Canada. However, it has not announced a partnership with any US carriers yet.

Lynk currently has three satellites in service, and commercial Lynk roaming service has so far only been made available in a few remote locations, such as the Solomon Islands.

Lynk still needs to demonstrate a viable path forward and justify the investment needed to build out the full Lynk constellation.

Skylo

The final company making headlines with consumer direct to cellular service is Skylo - which is powering the emergency satellite SOS features found in the latest Google Pixel 9 and the Samsung Galaxy S25 models sold by Verizon.

The final company making headlines with consumer direct to cellular service is Skylo - which is powering the emergency satellite SOS features found in the latest Google Pixel 9 and the Samsung Galaxy S25 models sold by Verizon.

Skylo does not own any satellites or spectrum of its own - but rather it is partnering with several legacy geostationary satellite providers (such as Ligado, Echostar, TerreStar, and Viasat) to use a slice of their spectrum to bounce down a low bandwidth direct-to-device signal from orbit.

With Google on board and Verizon touting Skylo integration, other Android device makers will likely introduce Skylo reception capability in future hardware releases.

Any phones using the Qualcomm X80 modem chipset might have the potential to be made Skylo compatible.

Other LEO Constellations - Current & Future

Beyond SpaceX's Starlink and Amazon's Kuiper, other satellite constellations may someday prove viable for nomads.

Here is an update on a few of the projects on our radar....

OneWeb - Still Mostly Irrelevant

At one point, OneWeb actually looked likely to beat SpaceX in the race to be the first to launch a next-generation satellite constellation.

However, as we have covered extensively in the past, OneWeb has had an incredibly rocky road to launching its satellite broadband network.

OneWeb, in the early days, had plans to serve everyday consumers, but by the time OneWeb was ready for customers in mid-2023, SpaceX had a dominant lead.

Now, OneWeb is primarily focused on providing satellite options to governments, cellular carriers (as tower backhaul), airlines, and other large enterprise customers.

In 2023, OneWeb merged with European satellite company Eutelsat, allowing Eutelsat and OneWeb to create solutions combining traditional geosynchronous (GEO) satellites with the low Earth orbit (LEO) OneWeb constellation.

For our audience of consumer RVers and boaters, OneWeb has seemingly become irrelevant.

However, in the future, the combined resources of Eutelsat and OneWeb might prove interesting again. OneWeb is still working towards a second generation GEO/LEO hybrid constellation - but the earliest it will be ready for service seems to be 2028.

OneWeb is also partnered with HughesNet (discussed below), and HughesNet may eventually offer a hybrid GEO/LEO service as well.

Iridium Project Stardust - Wishing For A Partner

Iridium pioneered using a constellation of low Earth orbit satellites to provide truly global coverage - focused at first on satellite phone calls and very low bandwidth data connections.

The first generation Iridium satellites started launching in 1997, and the network was completed in 2002. It was way ahead of its time!

The second-generation Iridium Next constellation added more data capabilities. It began launching in 2017 and came online in 2019.

Iridium is the technology behind a wide range of satellite communicators and other low-bandwidth mobile devices.

But to try and remain relevant into the future, Iridium in early 2024 announced Project Stardust to repurpose the existing Iridium satellites to enable integration with 5G-based satellite messaging and internet-of-things applications.

The catch with Project Stardust is that it will not work with existing phones, and new hardware is required on the receiving devices.

Iridium has said that it hopes to begin testing Stardust in 2025, with service coming in 2026—assuming device manufacturers cooperate and integrate compatibility.

So far, there are no publicly announced partners.

Other Satellite Internet Constellations

Here are some potential future satellite projects we have on our radar.

Most of these are targeting enterprise, government, or foreign markets, but some may eventually evolve to be interesting to our broader nomadic audience:

- Telesat Lightspeed - Lightspeed is a perpetually delayed satellite constellation that will feature laser links between satellites. This constellation is not currently consumer-focused, and the most recent first launch estimate is no sooner than late 2026. One primary market for Telesat at the moment seems to be providing satellite backhaul to traditional cellular carriers building towers in remote locations. So indirectly, Telesat someday may play a role in keeping many nomads connected.

- E-Space - E-Space (in partnership with the government of Rwanda) raised eyebrows in 2022 by filing to secure a license to operate a future constellation consisting of 327,320 (!!!) tiny satellites. Everything about E-Space sounds absolutely over the top - but it is fronted by well-respected space industry veteran Greg Wyler, who was the original founder of OneWeb. E-Space actually launched three test satellites, but no further updates have been published in the past year.

- Ligado SkyTerra - The geostationary SkyTerra 1 satellite launched in 2011 with the “largest reflector (22 meters) in service on a commercial satellite,” and it was designed to theoretically enable low-bandwidth communication directly to small devices like phones. However, Ligado has been struggling to get device manufacturers to build support for its signal, and the Department of Defense blocked Ligado's plans to supplement the satellite with ground-based signals for extra capacity because of concerns that there might be GPS interference. In early 2025, Ligado declared bankruptcy, and it looks as if AST SpaceMobile will be swooping in to grab up Ligado's spectrum rights for future D2D services.

- Rivada Space Networks - Rivada claims to be building a 600-satellite constellation with laser interlinks, with deployment slated to start sometime in 2025. Rivada bought up the old spectrum rights held by defunct satellite company Trion Space, and because of this, Rivada claims that its satellites will have spectrum priority over both Amazon and SpaceX whenever their orbits conflict, potentially giving Rivada a competitive advantage. Rivada's stated goal is to provide wholesale satellite capacity to other companies. It will be interesting to see if anything worthwhile comes of this corporate maneuvering to claim priority spectrum. So far, Rivada seems to be going nowhere fast.

- Logos Space - A new entrant aiming to build a 4,000+ satellite constellation, with a focus on security and resistance to jamming and "electronic warfare". Target markets are governments and large enterprises.

- European "Starlink Competitor" - The European Union announced in 2023 that it was funding a consortium of European satellite companies to work together to build a sovereign European-controlled Starlink competitor, with an ambitious (and likely unrealistic) goal of being ready for service in 2027. Though details remain sparse, if and when this constellation comes online, it may prove to be primarily focused on military and government traffic and not on the consumer market.

- China's Megaconstellations - Chinese company Shanghai Spacecom Satellite Technology has raised nearly a billion dollars towards a planned 12,000 satellite mega-constellation designed to compete with Starlink. The first 18 were launched in August 2024. Additionally, the China Satellite Network Group announced a similar 13,000-satellite project. These projects are likely dependent on China's perfecting a reusable rocket launch system, which has been in testing.

Some of these projects will likely never get off the ground, and of those that do, we expect that few will have the ambition or scale to target a broad mobile consumer market.

But one thing is certain—the skies will be getting crowded, and connectivity everywhere will become increasingly capable over time.

Legacy Satellite Still Stumbling

While OneWeb, Starlink, and Kuiper aim to circle the globe with hundreds or thousands of small low-earth-orbit (LEO) satellites, the traditional satellite industry remained focused on building a small number of gigantic, super-capable satellites in geosynchronous orbit, servicing an entire continent at once from thousands of miles overhead.

On paper, this seemed like a smart strategy. But in practice, these giants have stumbled badly.

ViaSat - Still Slipping Schedules

Legacy satellite broadband leader ViaSat (formerly known to many as Exede) announced in 2015 that it was aiming to deploy a new geostationary constellation consisting of three absolutely gigantic ViaSat-3 satellites to deliver next-generation performance around the world, starting in 2019.

When ViaSat-3 was originally proposed, each of the individual planned ViaSat-3 satellites was designed to have more raw data capacity than ALL other commercial satellites currently in orbit, combined!

But after years of delays, when the first ViaSat-3 was launched in April 2023, the satellite failed to deploy its gigantic antenna properly.

ViaSat is still regrouping from this failure. The remaining two satellites have slipped to allow time for design changes and are now targeting a launch no earlier than Q3 2025.

Even if these giants eventually work as planned, will they matter in a world dominated by Starlink and other more nimble competitors?

To remain relevant, ViaSat also purchased and merged with British satellite communications company Inmarsat.

Inmarsat has long been a leader in legacy low-speed satellite voice and data (particularly in the marine market), and now, combined with ViaSat, it is pursuing long-term plans to enable satellite-to-cellular connectivity with its own hybrid LEO/GEO architecture.

Will it all ultimately be too little, too late?

HughesNet - Slowly Fading Away?

Back when MIRC first launched, legacy satellite pioneer HughesNet was pretty much the only game in town for nomads in remote locations looking to keep connected.

But as cellular, Starlink, and other broadband options have reached more of these isolated areas, customers have been abandoning HughesNet.

Hughes once hoped that the much more capable Jupiter 3 ("the world's largest and most advanced commercial communications satellite") would change the equation—as would the Hughesnet Fusion option, which combined the raw speed of satellite with the lower latency of cellular.

However, the consumer HughesNet service requires a two-year contract, professional installation, and a fixed location with a traditional dish. For Fusion service, you need to be in an area with a cellular signal on a HughesNet partner to provide the low-latency uplink connection.

In other words, the current HughesNet service is NOT mobile-friendly for RVers and boaters.

Looking further into the future, Hughes is an investor in and partner with OneWeb, and there still appear to be long-term plans to bundle OneWeb service and HughesNet service together in ways that combine the low latency of LEO with the raw, focused capacity of GEO.

This is likely years away, but it might prove to be very interesting once this hybrid technology matures and, hopefully, becomes available for mobile users.

But overall, HughesNet looks like a dinosaur in the new era of satellite broadband options.

Concluding Thoughts

Cellular and satellite technologies are growing closer and closer together, and the big companies continue to partner up.

Just consider the direct-to-cellular options:

- T-Mobile - Partnered with SpaceX for Starlink Direct to Cell.

- AT&T - Partnered with AST SpaceMobile.

- Verizon - Partnered with AST SpaceMobile, but also partnering with Skylo for emergency messaging and Kuiper for tower backhaul.

- Apple - Working with all the carriers to support its own satellite messaging initiatives, plus using GlobalStar to enable its own satellite messaging.

- Google - Working with Skylo for emergency messaging on Android.

For those looking for mobile satellite broadband options, Starlink is currently the clear choice for most of the consumer market.

Hopefully, Amazon will soon have a worthy offering in Kuiper that dials up the competitive heat.

This is what the future looks like - connectivity everywhere!

But behind the scenes, it is more complicated than ever before.

For those who seek to stay connected, it makes sense to stay tuned to this exciting race and embrace all your options!

Further Reading

- Starlink Satellite Internet For Mobile RV And Boat Use - Our featured guide focused on taking advantage of SpaceX's Starlink on the go.

- Mobile Satellite Internet Options -

Our featured guide on all the current and future satellite internet options of interest to RVers and cruisers.

Our featured guide on all the current and future satellite internet options of interest to RVers and cruisers. - All our Satellite Internet Resources - Our collection of guides, gear center entries, and news coverage on satellite internet.

And here is all of our recent satellite internet coverage:

Mobile Internet Resource Center (dba Two Steps Beyond LLC) is founded by Chris & Cherie of

Mobile Internet Resource Center (dba Two Steps Beyond LLC) is founded by Chris & Cherie of